Introduction

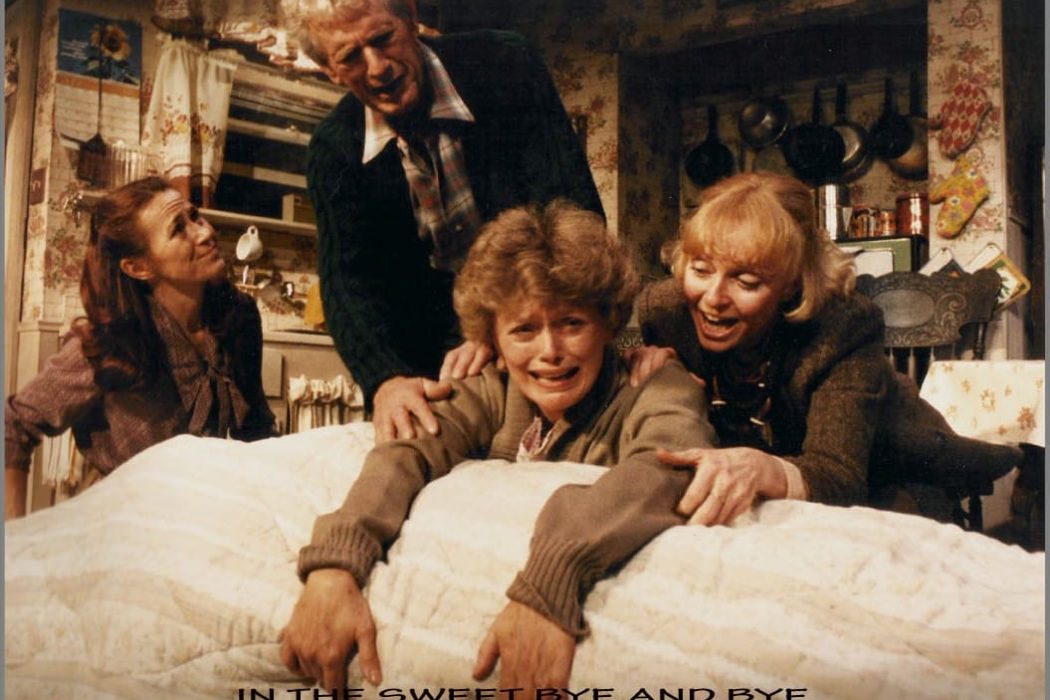

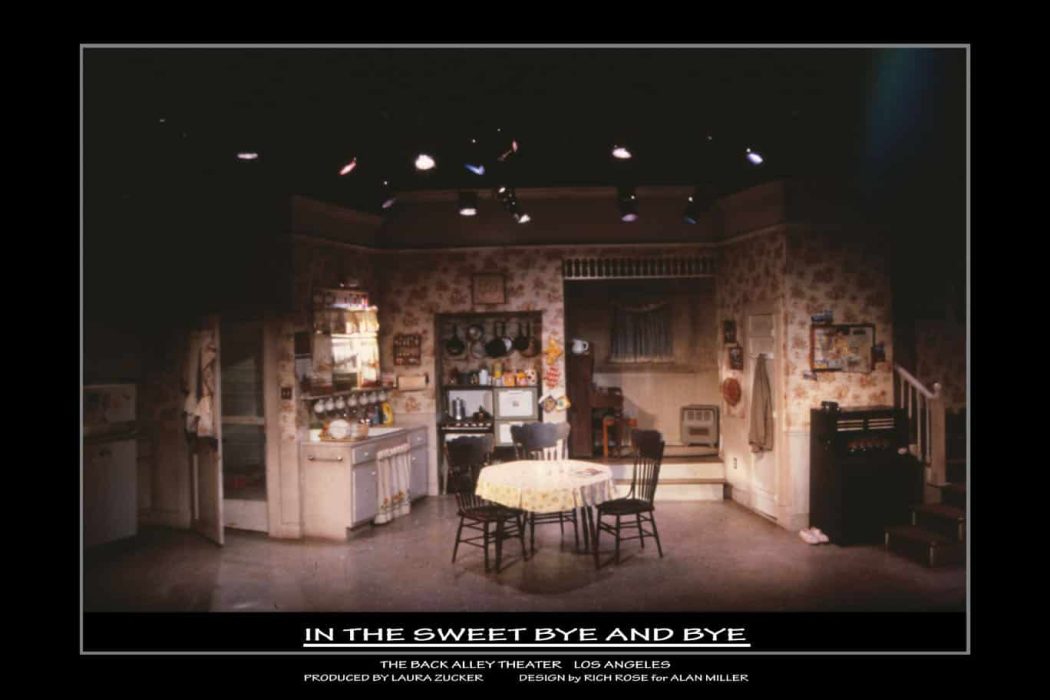

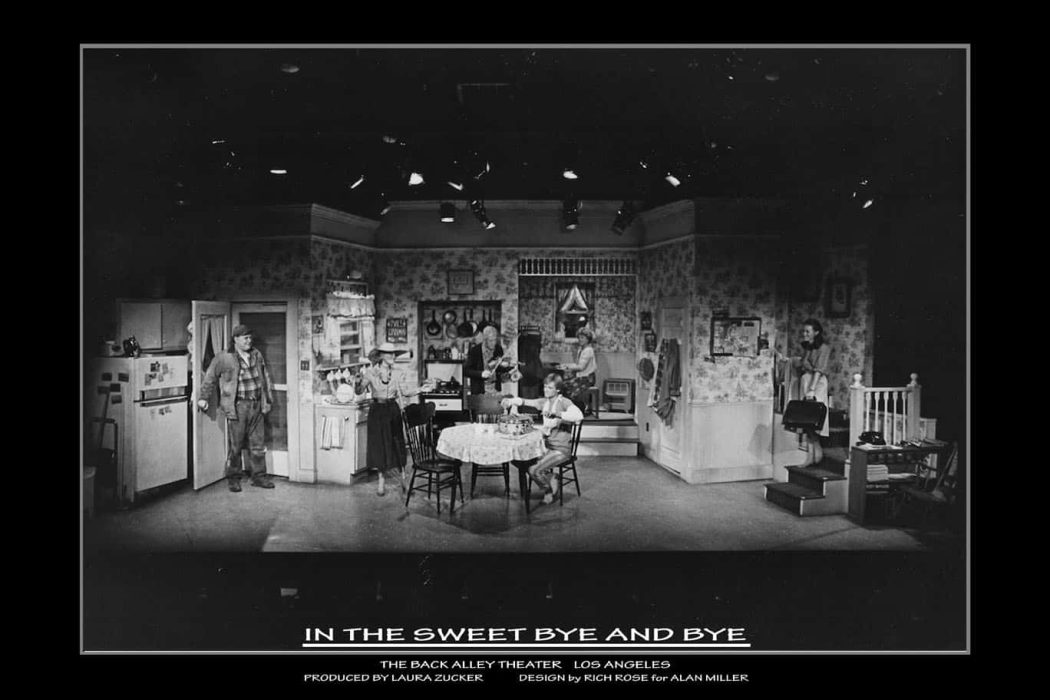

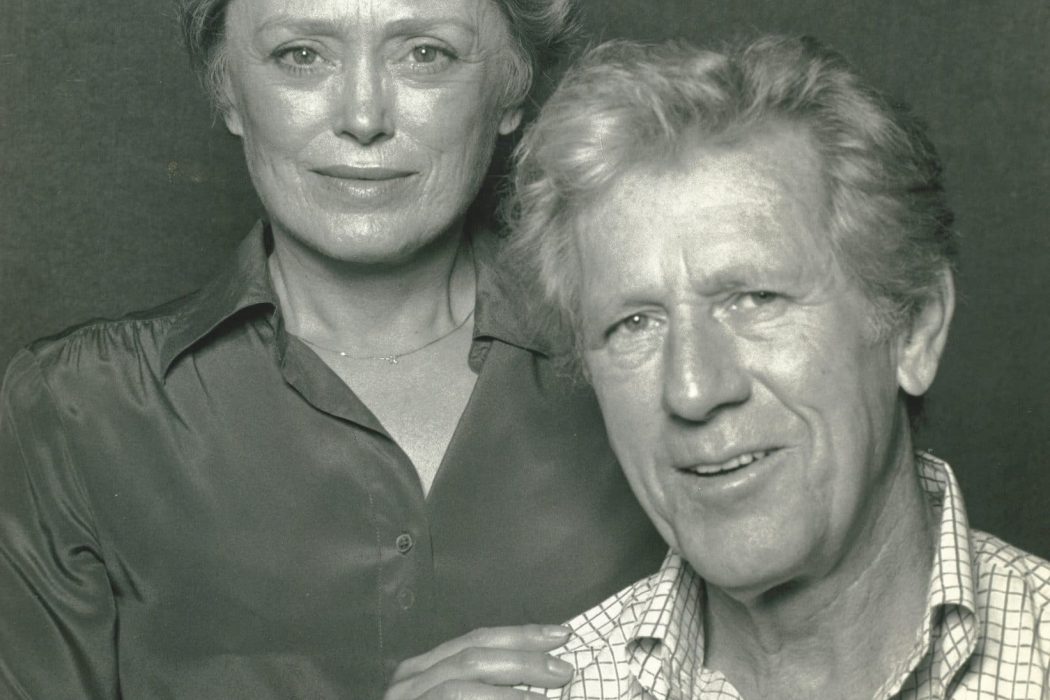

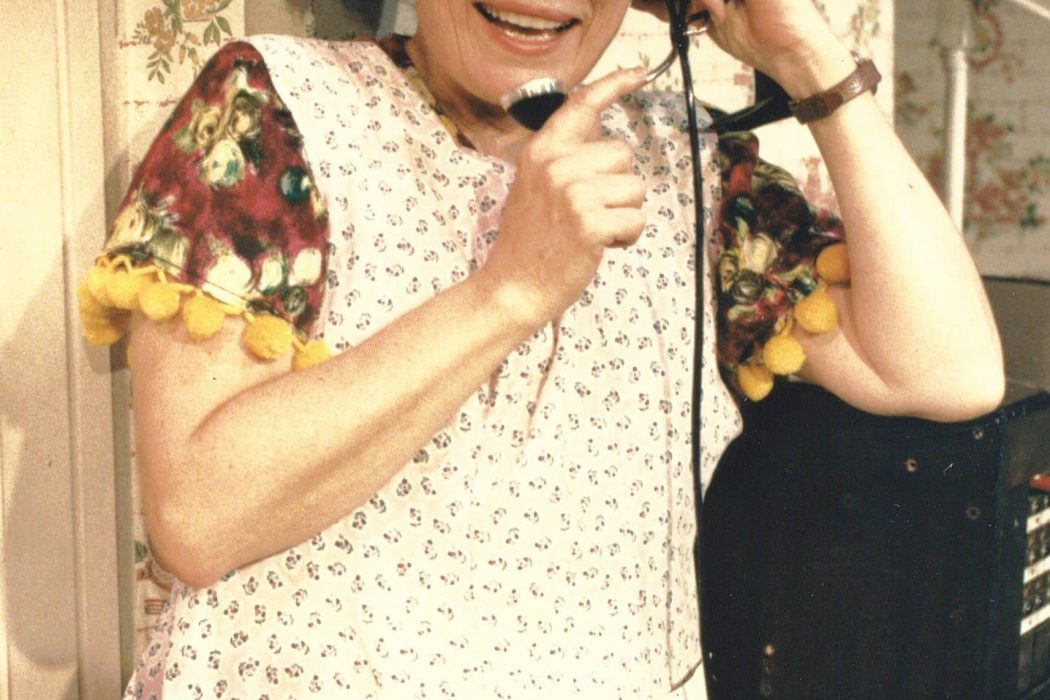

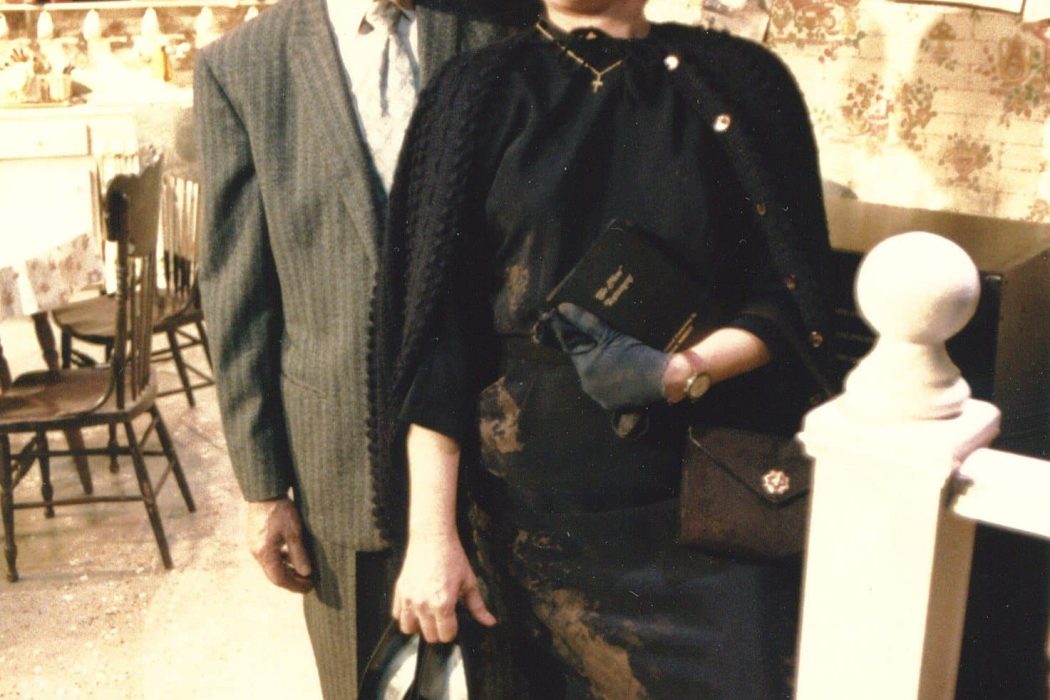

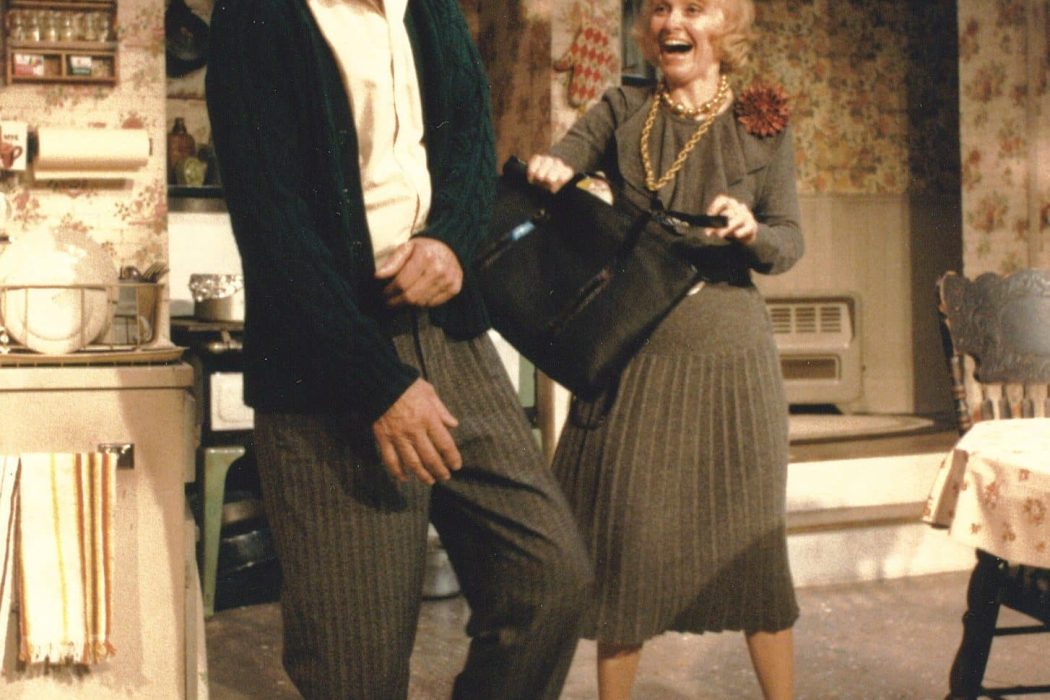

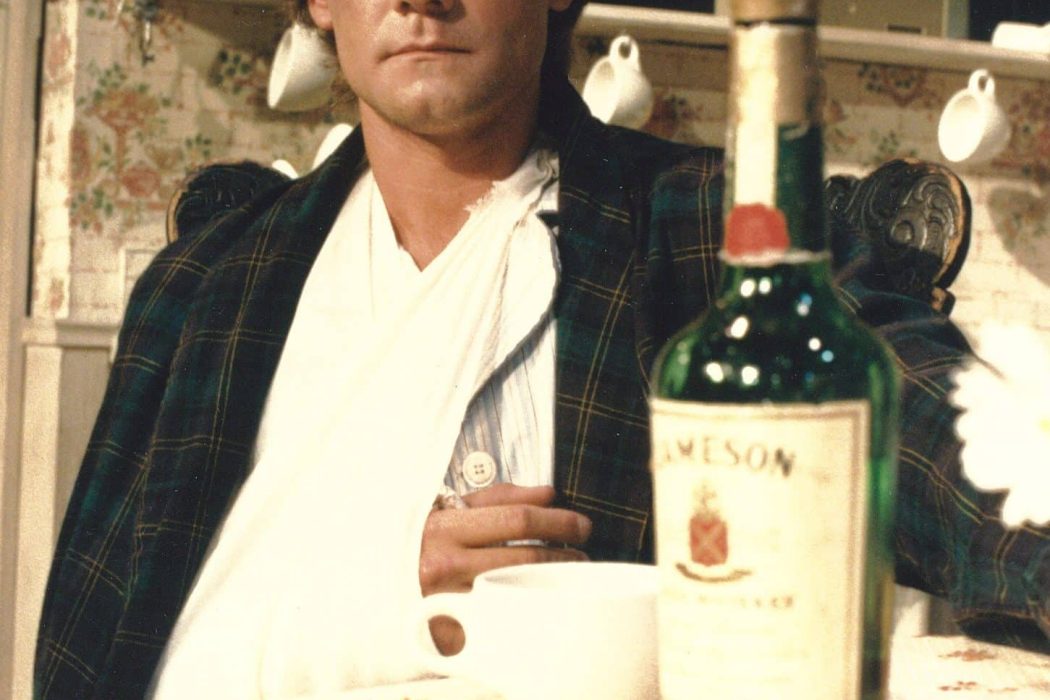

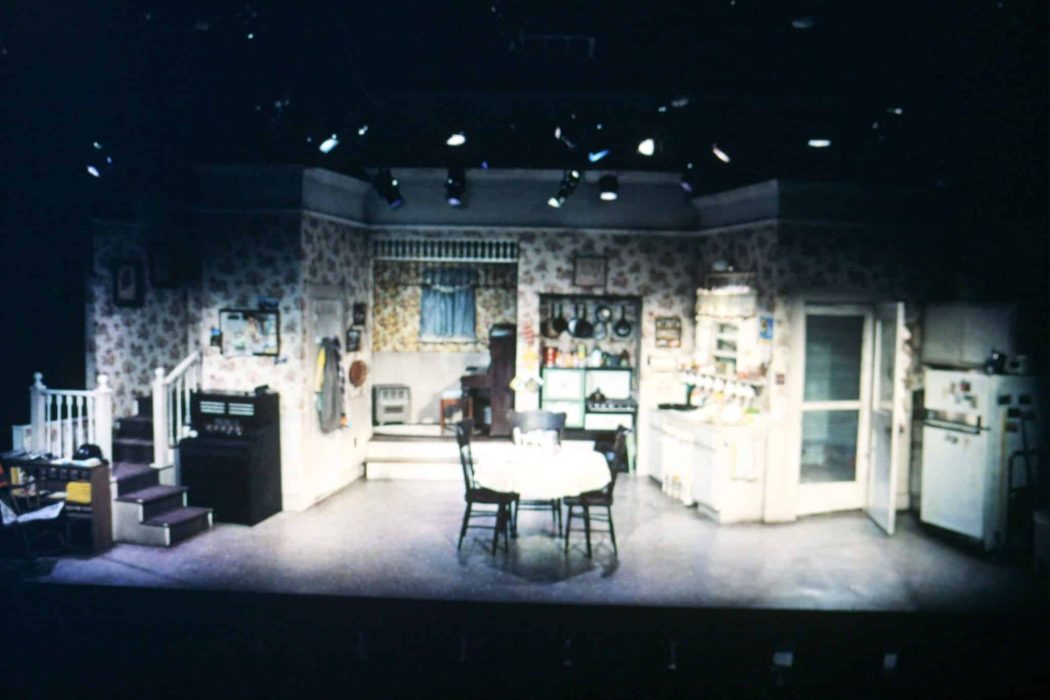

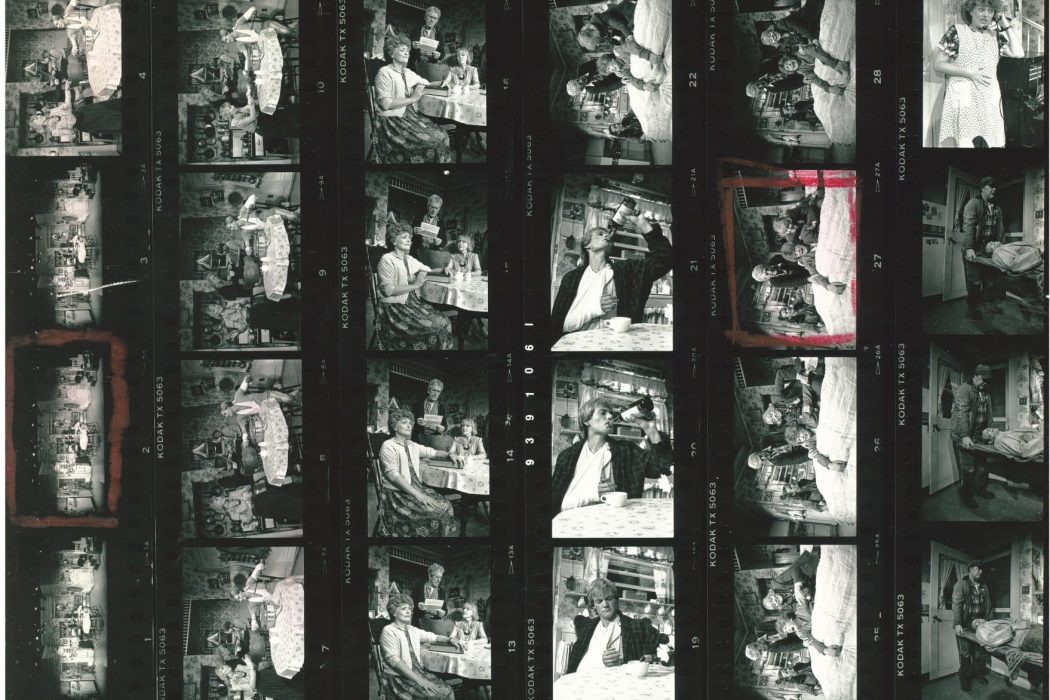

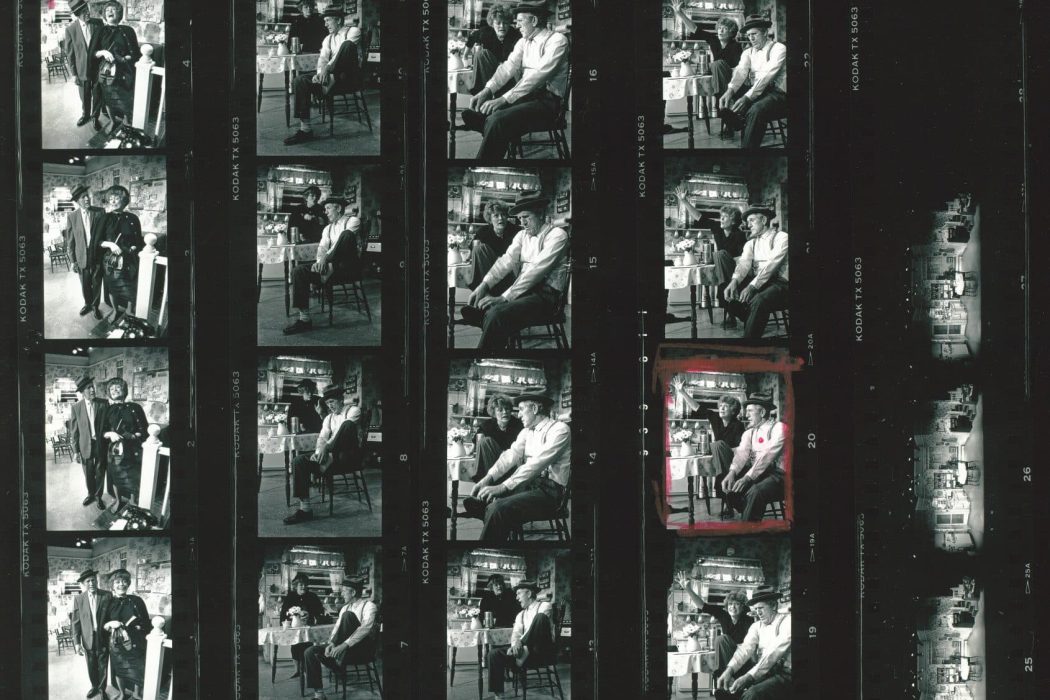

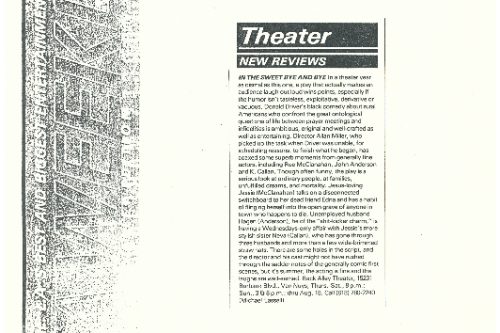

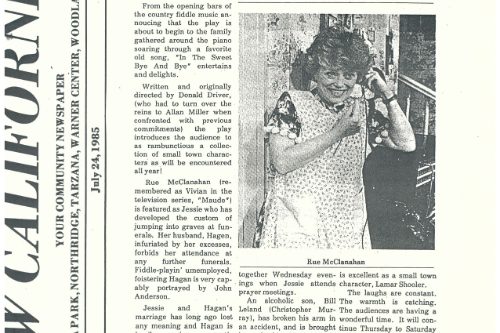

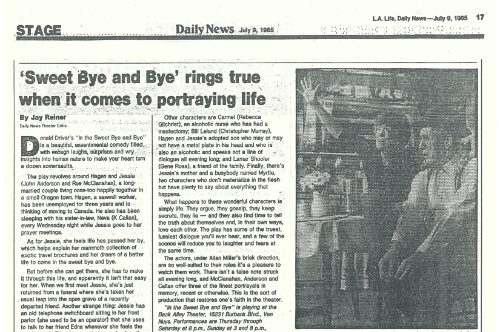

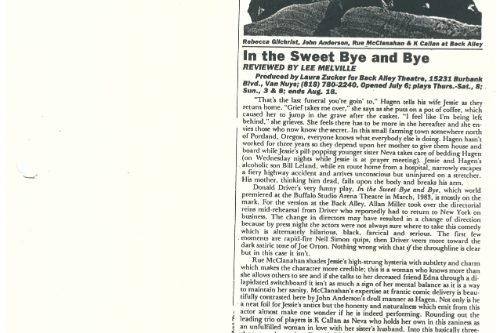

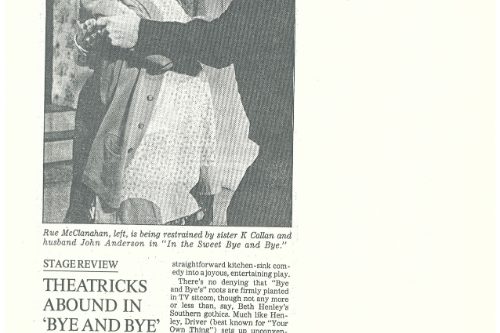

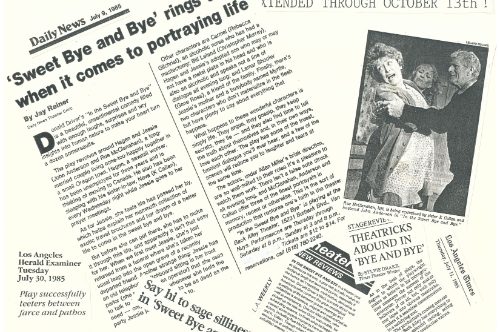

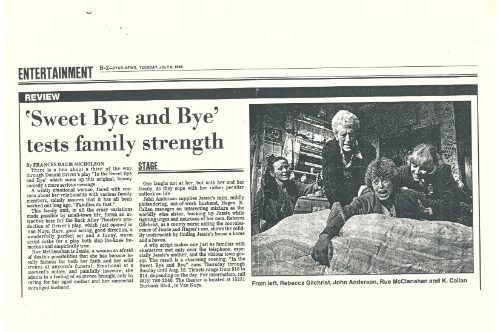

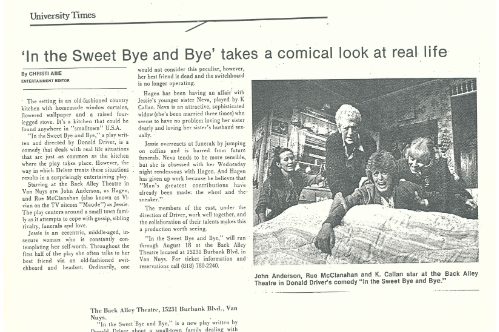

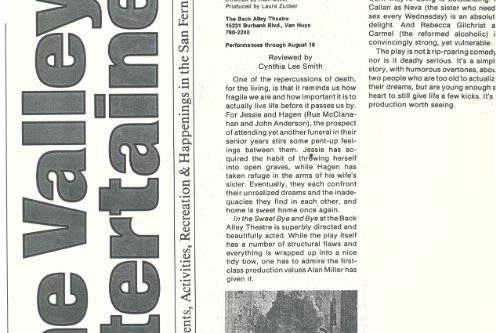

The longest, loudest laugh I’ve ever heard in a theatre was in IN THE SWEET BYE AND BYE by Donald Driver, which we produced at the Back Alley in 1985. Here’s the set-up: at the play’s opening, Jessie, played by Rue McClanahan, her husband (John Anderson) and sister (K Callan) are returning from a funeral where Jessie once again has thrown herself into a grave in a paroxysm of grief. Covered in mud, she insists she’s just slipped and fallen. Toward the end of the first act, she sees her injured son (Christopher Murray) stretched out in the middle of the kitchen by his nurse (Rebecca Gilcrest). We know he’s just passed out drunk; she thinks he’s dead. The audience starts to get what’s about to happen. As they see Rue beginning to moan and wail, twisting one way, then the other, they start to chuckle. As she winds up, the laughter grows. As she launches toward her son and flings herself atop him, the crate he’s lying on, which has been rigged by set designer Rich Rose, collapses and WHAM, the house explodes. I saw the show, which was a big hit and which Allan directed, a lot, mainly because I could never get enough of this moment.

Sylvie Drake described the play in the LA Times has having, “a deliberate affection for contradiction. Everyone in this mini-tornado of a comedy is a paradox and the quirkiness converts Driver’s straightforward kitchen-sink comedy into a joyous, entertaining play.”

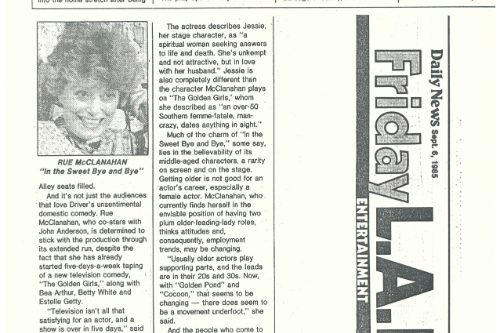

Rue was well known for “Maude,” which ran from 1972-78, but her career was in a bit of a trough when she agreed to do IN THE SWEET BYE AND BYE. Rue described Jessie as, “a spiritual woman seeking answers to life and death. She’s unkempt and not attractive, but in love with her husband.” As it happened, right after we began rehearsals, she got this new show called “The Golden Girls,” and began shooting while we were still running (the terrific Pat Huston sometimes covered for her when shooting ran late). Rue’s character in IN THE SWEET BYE AND BYE was the antithesis of Rue’s in “The Golden Girls,” but both shows were unusual in featuring actors in their 50s and 60s in the leads, and she often said how much she loved getting to do both at once.

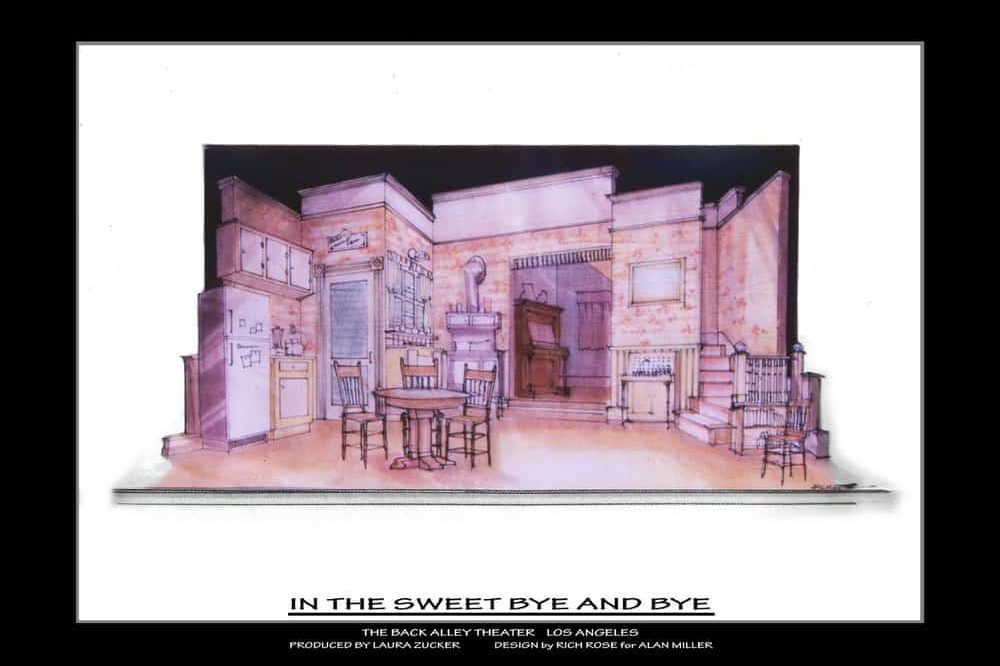

The Back Alley had a large stage and high ceiling for a smaller theatre, but, of course, we couldn’t fly anything in or afford a revolving stage, so we had to rely on creativity to solve scenic challenges. At one point in the play the entire set has to look as though it’s been re-wallpapered without an act break. One reviewer said the “living room transformation must be the scenic feat of the season.” How’d we do it? The “old” wallpaper was on panels Velcro-ed onto the “new” paper. Within a 30 second blackout, a synchronized crew that had been rehearsed until they could do it blindfolded, ripped the covering panels off and when the lights came up, voila! This usually got ooohhhs, music to a producer’s ears.

–Laura Zucker